Export delays loom as empty shipping containers pile up

8th Sep 2021

Original Article by Nikki Mandow from Newsroom

Nikki Mandow is Newsroom's business editor and the 2021 Voyager Media Awards Business Journalist of the Year - @NikkiMandow.

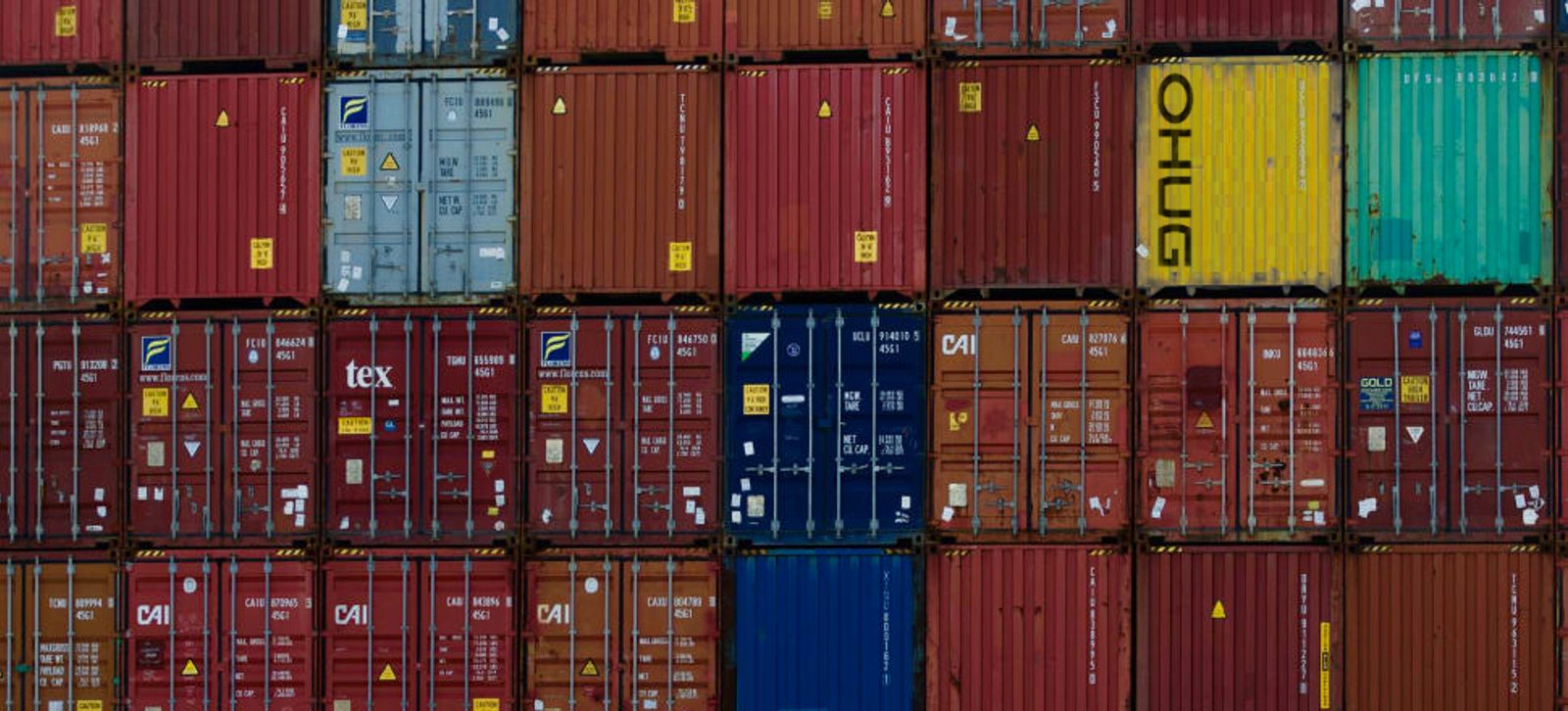

Upwards of 30% of shipping containers move in and out of New Zealand empty. Shipping chaos means they are piling up in yards. Original Photo: John Sefton

Strange but true: A surfeit of the wrong sort of empty shipping container could put our peak summer export trade at risk. Here's how.

Ken Harris is worried. The boss of ContainerCo, one of the biggest shipping container handling businesses in New Zealand, has never seen things so congested, so delayed. So many containers in limbo, waiting for shipping.

These containers aren't full of stuff. They are empty, clogging up his yards.

And the problem? Massive international demand for goods - and shipping bottlenecks all over the world - mean Harris is having big problems getting rid of them.

Unless the situation eases – and it’s at heart an internationally-fuelled crisis, although there are structural problems at home too and the Level 4 lockdown isn’t helping - Harris and others worry there aren’t going to be enough containers ready to take get our dairy, meat, fruit, vegetables and other exports out of the country when the busy time comes.

And that's just a few weeks away.

Most people never think about shipping containers, and that's just how Ken Harris likes it. But he explains that winter is traditionally off-season in the container business. Dairy and horticulture are quiet and the pre-Christmas import rush hasn’t started.

Winter is a time to get shipping containers ready for the busy season ahead. Photo: Supplied to Newsroom

At Harris’ seven container yards, and those of his competitors, winter is a time to clean and repair containers, get surplus empty import units back overseas out of the way, and start gathering and stockpiling the empty export containers we are going to need for the busy export period.

You heard right. Harris is sending empty containers out and stocking up on other empty containers coming in. On the surface it makes no sense. Until you know that there are shipping containers... and shipping containers.

At one end there are the bog standard lower grade ones that can transport not-too-fragile, non-perishable goods - all that extra stuff we’ve been ordering since Covid stopped us spending money on travel and dining out. Shoes, clothes, garden furniture, toys, gadgets.

At the other end there are the high-grade ones taking our primary produce overseas. Fruit and vegetables, dairy products, meat and seafood. And they are mostly a superior breed of shipping container. Many of them are refrigerated, temperature monitored. Even when that’s not necessary, to carry food they have to be well-maintained, spotlessly clean, often specially lined.

Imagine an old shipping container being like your fridge when the seals start deteriorating. One rusty hole at the top of a worn container can be enough to let heat or moisture in that could spoil a whole export load.

And much of our primary produce is pretty fussy about its travelling conditions. Seafood, the better cuts of meat, avocados, even onions, have to be kept at a constant temperature and / or humidity, even as the ships carrying our exports travel through the hot, damp regions around the Equator.

Who knew onions would be so particular about how they are transported?

Empty boxes on the move

Industry figures show around one million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units - the shipping industry’s standard measurement for containers) come into New Zealand each year. Around one million leave the country. But the same ones coming in full of toys often aren’t leaving full of apples.

Craig Harrison, national secretary of the Maritime Union of New Zealand reckons around 30 percent of container movements in this country are empty boxes.

“Auckland is renowned as one of the biggest exporters of fresh air.”

Craig Harrison, MUNZ

Analysis by shipping company PF Olsen in 2017 put the figure even higher.

“Due to New Zealand's trade balance, 70-80 percent of shipping containers are returned empty to offshore destinations,” the company said.

“Auckland is renowned as one of the biggest exporters of fresh air,” Harrison jokes.

And of course you have to pay to move containers around - even empty.

And that's where Ken Harris hits his problem. Global shipping chaos mean his container yards, particularly the ones in Auckland, are full of empty lower grade containers he can’t get out of the country.

That leaves no room for the refrigerated or other higher grade containers his export customers are going to need when the season heats up after Christmas.

Most of ContainerCo’s container servicing facilities around the country are operating “well above efficient volume levels, with several key yards holding over 130 percent of nominal capacity”, Harris says.

And that's not just frustrating, it's unproductive. Imagine your fridge again. If it’s full to the gunnels, it’s really hard to get food out from the back.

Same with a container yard, Harris says. Not only do his piles of surplus-to-requirements empty import containers leave no room for export containers, they also make it harder to operate the site efficiently.

Container yards operate best at 80 percent capacity. Some of ContainerCo's are at 130 percent. Photo: Supplied to Newsroom

To get one container out, you have to do a lot of shuffling of other containers in an increasingly limited space.

Add to that ContainerCo’s workforce has been reduced 10-12 percent by the present Covid lockdown, mainly staff impacted by locations of interest, or in the vulnerable worker category, and it’s increasingly tough to get ready for the export season.

Harris isn’t the only one worried.

Harriet Shelton is manager, supply chain, at Te Manatū Waka Ministry of Transport.

She says it’s touch and go whether there will be enough containers for the export season.

“It’s not a comfortable situation, and there will be some impact. We’ve seen it already in higher costs. Very much higher costs.”

Rosemarie Dawson, chief executive of New Zealand’s Customs Brokers and Freight Forwarders Federation, goes further. She believes there is a 100 percent chance New Zealand’s exports will be affected. The unknown is how badly.

“We might see growers closing, taking trees out, or growers not planting produce.”

There are a lot of nervous people, says Craig Harrison. People worried they aren’t going to have the containers they need.

Congestion on a global scale

So what’s happening? What’s gone wrong this year?

In a normal year, say the experts, the disconnect between the containers bringing imports into New Zealand and the ones we need to take our exports out, doesn’t cause problems. Ships pootling around the world have the capacity to carry empty containers as well as full ones. Fresh air isn’t as lucrative for a shipping company as full loads, but it’s part of the deal.

Not this year. Eighteen months of Covid around the world has played havoc with international shipping.

On the demand side, everyone is buying more stuff - so there’s more stuff to move.

On the supply chain side, each time a Covid outbreak closes a port somewhere in the world or social distancing reduces the number of workers able to load and unload cargo, the existing delays get a little bit worse.

Earlier this month, for example, a Chinese dockside worker testing positive for Covid shut a key terminal at the third largest cargo port in the world, Ningbo-Zhoushan.

All around the world, dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of container ships are anchored up outside ports - sometimes for days at a time - just waiting for their space to dock, unload some cargo and load up some more.

Some container ships are waiting days before being allowed to unload cargo in Auckland. Photo: John Sefton

Take your daily lockdown walk up to Auckland’s Bastion Point lookout, and you can see the ships here too, waiting off Rangitoto Island.

It’s not just Auckland. Shelton of Te Manatū Waka Ministry of Transport, says: “I was in Tauranga recently and I climbed Mt Maunganui. I counted nine bulk and container ships anchored offshore.”

She estimates there are around 350 ports around the world experiencing delays.

“Ports publish their waiting times. It could be four days, seven days, sometimes even 10 days.”

Some ship owners facing several days of delays at each port on the way to New Zealand, simply decide not to visit New Zealand, or to visit less often, or to spend less time here by missing some ports off their schedule, Maritime Union’s Craig Harrison says.

“We are hearing stories of a ship scheduled to go to Napier, which just cancelled Napier, and instead went to Timaru. If you are a little vineyard or a niche exporter and you’ve spent money getting your container to Napier, what do you do? This could push you to the point of tipping over if can’t get your product to market.

It’s one of the hazards of being a small, far-off export country in a super-tight market.

Shanghai's Yangshan port can handle ships with 22,000 TEUs on board. In New Zealand, the vast majority are under 8000 TEUs. Photo: Getty Images

“In one of the high-yield Northern Hemisphere regions, a shipping company might be able to deliver 9000 containers to just one port. In New Zealand it might be just 6000 containers and the ship will have to go right round the country.

It’s not surprising New Zealand’s empty containers aren’t a priority.

“Imagine I’ve got my ship coming into port, but I’m delayed - I’m getting behind. I was supposed to pick up 400 empty containers, but I’ve run out of time, so I just load on the containers with freight, but not the empty ones.”

Little by little uncollected containers pile up, he says.

“As each ship over the last 18 months leaves 100 behind, or 50 behind, it starts to build. That’s why we have container yards at 130 percent capacity.

“Ships are diverting to Tauranga and now it’s starting to fill up there too.”

A shipping company’s market

New Zealand accounts for only 0.5 percent of global shipping traffic, according to KPMG’s latest Agribusiness Agenda report.

It’s a “precarious situation”, the report says, given we are a pretty insignificant place for international shipping companies, yet we are so reliant on these shipping giants to get our exports out. This might not matter too much in normal times, when any business is good business for shipping companies.

But this is a boom time and shipping companies can pretty much go where they like and charge what they like. And they are reaping the benefits after some lean times in the past.

New Zealand isn’t a priority.

Even our largest port, Tauranga, can't provide the volumes big shipping companies want. Photo: Lynn Grieveson

Take AP Moller-Maersk A/S, the world’s biggest container shipping line. At the beginning of 2021, analysts were forecasting full year operating profits of around $US4.5 billion, according to a report from Bloomberg.

A few months later and the Danish shipping giant is now predicted to make around $US14.5 billion this year, Bloomberg says.

Meanwhile Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd AG has earned more in the past six months than in the previous 10 years combined.

“If freight rates keep rising, the container lines could collectively make $100 billion in operating income in 2021,” the article says, quoting Drewry Maritime Research. “For context, that’s more than 15 times the profits they generated in 2019 and nearly as much as Apple Inc makes in a typical year.”

An opinion piece in the Financial Times says what with Christmas boosting demand and Delta constraining supply chains, few in the industry expect international port congestion to clear, shipping containers to start moving more freely again, and freight prices to go back to anything like normal, until the first quarter next year - at the earliest.

And that’s bad news for New Zealand.

“Shipping companies can make more money on shorter runs carrying more containers,” Harrison says. “And as ships get bigger, so they wonder ‘Do we send as many ships to New Zealand?’”

The impact down under

As prices soar (shipping costs have quintupled for some exporters over the past few months, costs doubling is normal) and containers are increasingly in short supply, major exporters have already started to make plans.

T&G chartered the Cool Girl bulk refrigerated ship to take apples from Nelson to Europe. Photo: Supplied to Newsroom

As Newsroom reported this month, Zespri has chartered three bulk refrigerated ships to get kiwifruit to its Asian customers. Others in the "big end of town" - including produce company T&G Global, Affco meat and its sister company Talley's seafood - have also begun chartering conventional reefer (refrigerated) ships.

“There will be winners and losers. The smallest businesses will find it the most difficult."

– Harriet Shelton

But it’s going to be tougher for smaller companies, says the Ministry of Transport’s Shelton.

“There will be winners and losers. The smallest businesses find it the most difficult, as the larger ones have more flexibility, more of a buffer.”

And the Government? Is there anything they can do?

Government would rather not intervene, because it can end up distorting the market, Shelton says.

“We have thought about so many different options, but it comes down to providing tools for businesses to use - for example bringing data together on where availability is, where ports have capacity, or ships have capacity."

She says the ministry is also trying to encourage small exporters to join to share shipping space, particularly in bulk carriers, although collaboration isn’t the norm and doesn’t always come naturally.

Shelton believes, on the whole, exports will get out, one way or another. But it isn’t going to be easy.

“It’s going to be challenging and it’s going to be much more costly.”

NZ-flagged coastal shipping option

The Maritime Union’s Craig Harrison would like to see locally-crewed coastal ships moving empty containers out of crowded Auckland yards to other ports in New Zealand where they could be used or shipped out.

Since the domestic coastal shipping market was dereglated in the 1990s, empty containers tend to be shipped around New Zealand on the same big, international ships that bring goods in and out.

That was a cheaper option for businesses in quiet times, but it’s a big problem now there are shipping shortages, Harrison says.

These days, we have just one Kiwi-flagged container vessel, he says. There used to be nine.

"If we are going to meet our environmental goals, we can’t have 1000 containers going to the South Island on trucks.”

– Craig Harrison

The Maritime Union has been talking to Transport Minister Michael Wood about a coastal shipping and port strategy, Harrison says, including the idea of locally-based company Pacifica Shipping leasing a second domestic container ship to help get unwanted containers out of yards in Auckland and distribute them round the country. There they could either be picked up by international vessels, or used by regional exporters.

“We are saying it will give us resilience in supply - for example after earthquakes, when roads and rail are affected. Also, if we are going to meet our environmental goals, we can’t have 1000 containers going to the South Island on trucks.”

There used to be nine NZ-flagged container ships. Now there's only one. Photo: Supplied to Newsroom

But leasing a ship is expensive, Harrison says, and the local operator would be up against the international shipping giants which have size on their side and don’t have some of the costs (ACC or GST, for example) New Zealand players have.

“We are saying the Government needs to underwrite it or promote it to make sure it’s not undermined.”

Harrison says there has been some interest from the minister.

“Officials are starting to realise it’s getting dire.”

Pacifica Shipping says if it decided to go ahead, a new container ship could be operating in three months, in time for the summer peak season, Harrison says.

Another option to help ease the oversupply of import containers waiting to be shipped out would be more flexibility from shipping companies about what importers do with their empty containers, says Rosemarie Dawson at the Customs Brokers and Freight Forwarders Federation.

She says shipping companies insist shipping containers are delivered to a container yard, and charge importers if they hold onto them. But an option to deliver them straight to an exporter or hold them in their own premises would free up space in container sites, she says.

ContainerCo's growth options

Meanwhile, ContainerCo has dusted off expansion plans it had before the first Covid lockdown - only there’s more urgency this time, and more cost.

Harris says the company had previously delayed plans for major refurbishment at its Penrose and Oak Road, Wiri container parks in Auckland because it was worried about supply chain disruption.

“But with a return to normal shipping patterns looking unlikely for some years, ContainerCo has decided to progress this vital work,” he says.

The company is also looking to buy more land in Auckland, Bay of Plenty and Hamilton, but price hikes over recent months, particularly in Auckland, have made that hard.

The investment should increase ContainerCo’s Auckland yard capacity by 8-12 percent by April next year and potentially double the company’s capacity by 2027.

But in the short term, this summer will be tough, he says.

“It is costly and frustrating for importers, freight forwarders and transport companies when they are unable to return containers to designated container parks. It can be an even worse problem for exporters if the supply of containers suitable for exports is disrupted.”

Original Article by Nikki Mandow from Newsroom

Nikki Mandow is Newsroom's business editor and the 2021 Voyager Media Awards Business Journalist of the Year - @NikkiMandow.